A word about hats…

I love hats! To me there is nothing like a great hat to finish off an outfit. I think it’s really sad that hats are not more popular in this time period, for during most of our long course in history, hats were of great importance.

Millinery, which is the art of hat making, has existed as a trade in Britain since 1700, of course it was practiced for many centuries prior to that. It was a lucrative career and one that even a woman could pursue. Separate from the Milliner was the Plumassier, who specialized in plummage and the dyeing and arranging of feathers. Feathers were, of course, prized and very important, since no hat would be complete without at least one plume. The rich would pay a veritable fortune for an elaborately feathered hat and some sported entire stuffed birds; that was until the Audubon Society put a stop to that!

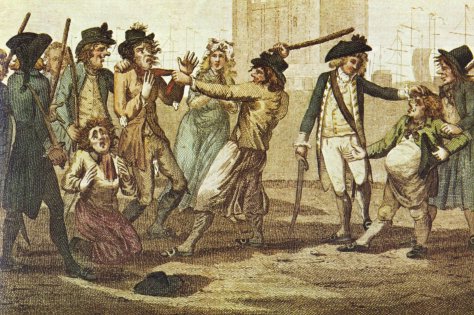

Hats have always been used to protect the head and keep it warm since much heat is lost through the top of ones head, however, hats have also, for many centuries been status symbols and fashion statements; there is nothing like a hat to draw attention to the face.They were large, small, plain and elaborate and were worn by both men and women. You would’ve known immediately what a man’s occupation was by the hat he wore, whether he was rich or poor, working or upper class. During the Regency period or Napoleonic era, a man of title or money would have worn a tall top hat or perhaps a bowler. It might have been made of wool, beaver fur or even horse hair. Sea faring men wore very distinguishable head gear with Captains wearing tricorns, bicornes, fore and afts or Chapeau de Bras. Hats represent authority and were and are today still a part of a uniform for military men, police officers and others.

For women however, hats are and have most often been, a fashion accessory. Much effort and expense went into the procuring of the perfect hat and it is by far the most important one that any person can wear. There is an old saying that says, if you want to get noticed or get ahead, wear a hat. I believe the pun is intended.

Head coverings were not limited to fashion only however, and during many periods of history, there was real etiquette involved in the wearing of one. A lady of any class and during most historical eras, would not have been properly dressed if she did not have something covering her head. This practice continued until as recently as the 1950s and 60s – my grandmother for example, would not have stepped into a church without a hat on her head. During the Victorian and Edwardian periods a woman would have been in disgrace if she did not cover her head even if it was just to post a letter. Only the poor or the peasants sometimes went without head gear and even women of that class often wore caps, which had the added advantage of keeping ones hair clean and tidy.

Hats have slowly lost popularity since about the 1920s, being used only for church attendance, weddings and other special occasions into the 1950s and 60s. Today, it is indeed rare to see an individual wearing a hat that does not serve a practical purpose, (unless of course if you are the queen) or isn’t part of a uniform. Sad but true.

One great thing of course about re-enacting or dressing in historical reproductions is that we can go a little hat crazy…